[ad_1]

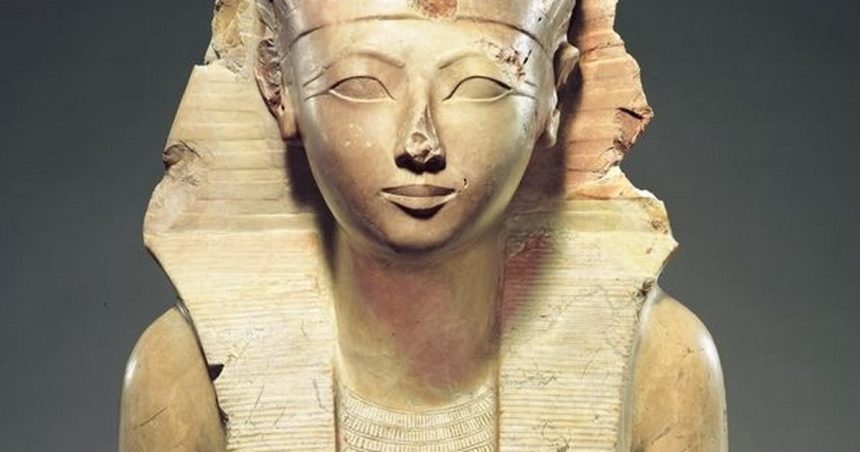

After three years as regent, she assumed the position of Pharaoh in her rights, becoming a co-ruler with her nephew. Her reasons for this action are still unknown, although speculations say that she decided to protect the throne from a political crisis. Because of her controversial assumption of the throne, Hatshepsut kept claiming that her father had appointed her his successor before he died; this claim was so that the people would agree to the legitimacy of the change in power. Upon assuming the full title and control as Pharaoh, she ordered statues be carved, representing her as a male king with muscles and beards; some feminine characteristics were, however, not easy to miss.

Hatshepsut’s reign was a relatively peaceful and less chaotic one. Her reign was filled with prosperity and the commissioning of numerous building projects. One of her biggest and greatest accomplishments was the construction of the great temple Deir el-Bahri at Luxor, which is considered today one of ancient Egypt’s architectural wonders of the world. Another great accomplishment of hers was the successful trip on the sea to the land of Punt(today’s Eritrea), a journey no other king had embarked on. Here, she traded with the people of Punt and brought back treasures of gold, ivory, incense, and ebony; she also brought back foreign trees to transplant to Egypt.

Hatshepsut died in her mid 40s in 1458 B.C. She was buried in the Valley of the Kings just behind the temple she had built. Thutmose III, who was technically her co-ruler, then proceeded to Pharaoh after her death. He sought to remove all traces and references to Hatshepsut’s successful reign by defacing her statues, images, and monuments so that he could make all her success his.

[ad_2]

Source link